Governments are acquiring and sharing more of our data on the basis that it will improve efficiency, personalise services, and reduce fraud, error and debt. Data acquired for one purpose is often used for another, whether the citizen agreed for this to happen or not – perhaps most notoriously our health records or children’s data.

In the background, technologies such as machine learning and artificial intelligence use these data to automate the rules, processes and decisions of the state despite evidence of the potential harm this can cause.

We can already see in the dominance of global technology companies such as Google and Facebook how such large-scale data acquisition and analytics puts them in an almost unassailable position. Left unchecked, technology will inevitably place governments in a similar privileged position, imperilling the essential roots of liberal democracy and the delicate balance between citizen and state.

The challenge to justice

Let’s consider a simple, but important, example of how this growing asymmetry will begin to disproportionately favour the state, and further erode the Rule of Law: criminal justice.

If the current trend continues, technology will provide the prosecution with near unlimited access to all the data available to the state – across the entirety of its own services and organisations as well as those of the private sector – and the compute power to mine, analyse and make use of it.

This could, if robustly regulated, be a good thing. It could help avoid miscarriages of justice by improving the discovery and use of evidence to establish innocence; or bring to justice those who might otherwise not have been detected.

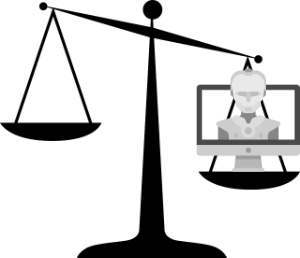

But what about the defence? What happens to the ideal of the balanced scales of justice, of the fair distribution of law – with no undue influence or bias, privilege or corruption – when the prosecution has such powerful, state-backed resources at its disposal? And who will objectively assess essential issues such as the quality and veracity of the data, and the efficacy of the algorithms used, including AI and machine learning, and any biases and other flaws they exhibit?

If governments continue on their current trajectory, without the implementation of better legal safeguards and transparency, technology will inevitably weigh the scales excessively in favour of the state. Justice will no longer be blind.

Unless the state is obliged to share the data, analytical tools and compute power with the defence, the state will occupy a privileged, and potentially corrupting, position. In the same way that it’s almost impossible for new entrants in the commercial marketplace to compete with global giants such as Google and Facebook today, tomorrow it will be impossible for defence teams to “compete” with the privileged technological resources of the state. The defence will lack the resources, data and analytical technologies to ensure due balance with those of the state unless we legislate and regulate for that to happen.

Our justice system is of course only one example. Similar issues arise across all areas where government provides services.

So what next?

We need robust laws and regulations – and meaningful enforcement – to ensure that private and public sector use of technology embeds and observes our existing rights. Anything else will weaken democracy by fracturing and weakening our rights.

We need robust laws and regulations – and meaningful enforcement – to ensure that private and public sector use of technology embeds and observes our existing rights. Anything else will weaken democracy by fracturing and weakening our rights.

Government needs to demonstrate that whatever technologies it applies, and whatever use it makes of citizens’ data, that it does not accrue any undue influence or bias, privilege or corruption. We also need our public services and the organisations behind them to ensure that no-one is disadvantaged by a lack of access to resources – including relevant data, analysis and computational power – or a lack of transparency and accountability.

The alternatives are already visible around us in the worst excesses of Facebook, Cambridge Analytica and the Chinese Government’s social credit system – and others, closer to home – as I’ve previously commented. The current criticism of global technology companies will pale into relative insignificance if these same behaviours are also adopted, unchecked, in the public sector.

Technology, used for good, could be a wonderful leveller. A guarantor of our democratic rights and liberties, ensuring citizens are as empowered as the state. It could help restore symmetry, taming the technology-enabled excesses of both commercial organisations and governments. If this is to happen, fixes to the growing democratic deficit are needed now.

Acknowledgments

Based on an original discussion with James Duncan.