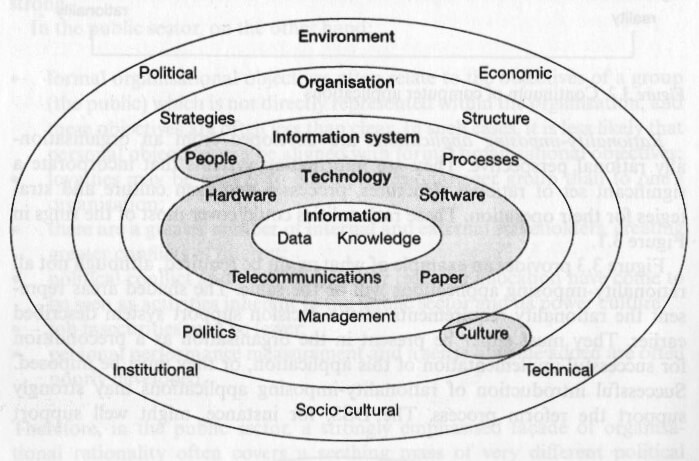

In the 1999 book “Reinventing Government”, information is placed at the centre of the government reform model:

The rings identify multiple aspects that need to be addressed when attempting reform. Yet many efforts focus almost obsessively on the “Technology” ring, implementing new ideas and approaches to hardware and software in particular in the hope that they will somehow magically ripple across all the other rings without any ability to explain how such a change will ever happen.

This technology-centric approach ignores the core of the model – information – and the many other rings (issues) that need to considered too. This is similar to the way that far too many Chief Information Officers (CIOs) blatantly ignore the ‘I’ in their title, and revert to focusing on technology, playing around in the weeds of tactical work such as PC upgrades and indiscriminate outsourcing rather than taking a leadership role in delivering fundamental service and organisational improvements.

“Build it and they will come” has become the tired mantra of various generations of central technology teams in Whitehall, despite the evidence that this approach doesn’t work.

The simplistic assumption has been that technology will help drive “… service organisations, including those in the public sector, towards profound transformations in the design of their production processes and structures.” [2] Yet as Margetts and Willcocks noted as long ago as 1993 [3], the public sector is particularly vulnerable to risks introduced by technology and at risk of “disaster faster”.

The role of technology in the best examples in the private sector has moved well beyond the automation or optimisation of existing processes, information management and services. The most significant changes have arisen from technology-enabled improvements to processes, organisational structures, functions, roles and services at all levels. Meanwhile, the public sector falls further and further behind, continuing to use technology largely to automate the past and to run in circles “rediscovering” the same things as the teams that went before.

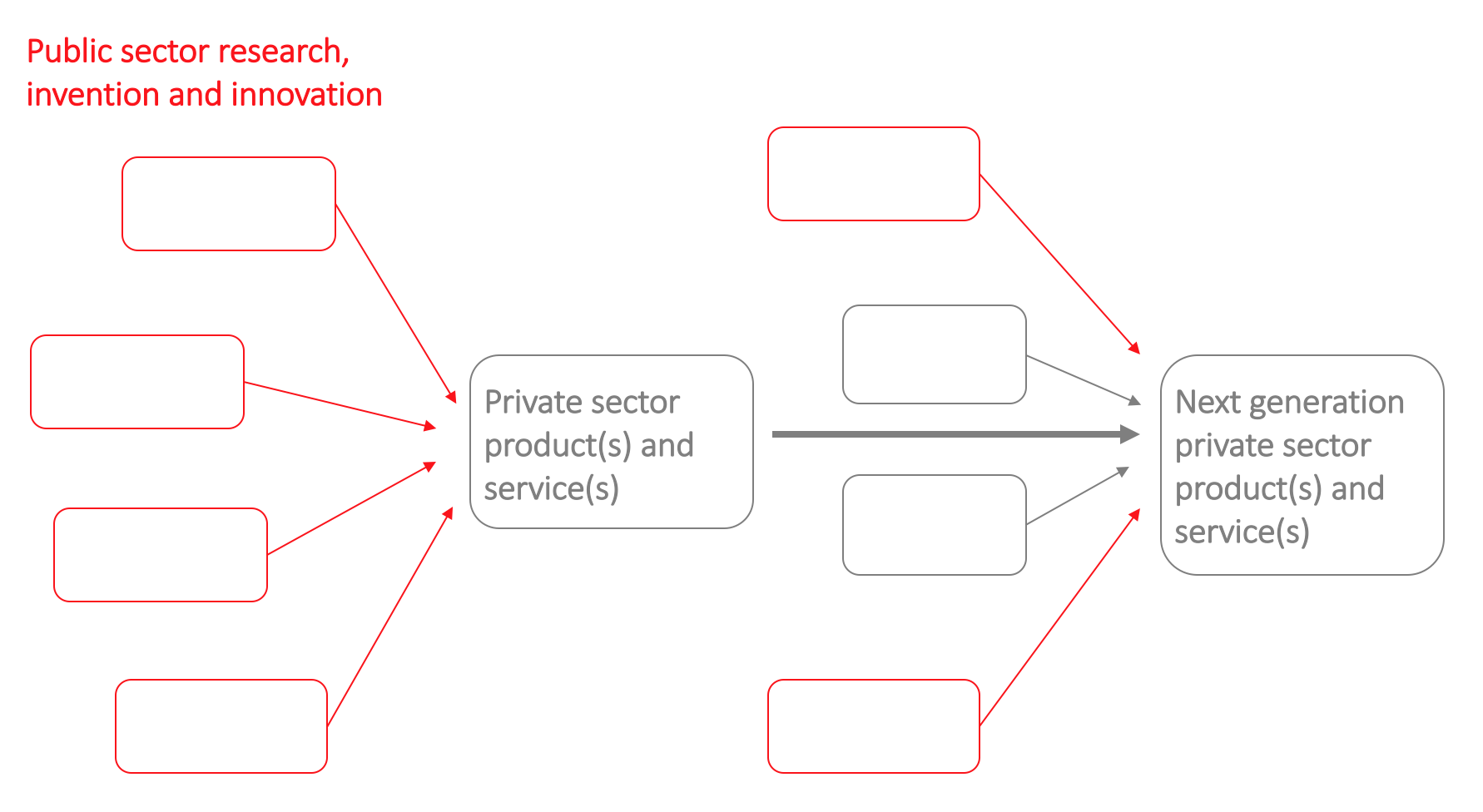

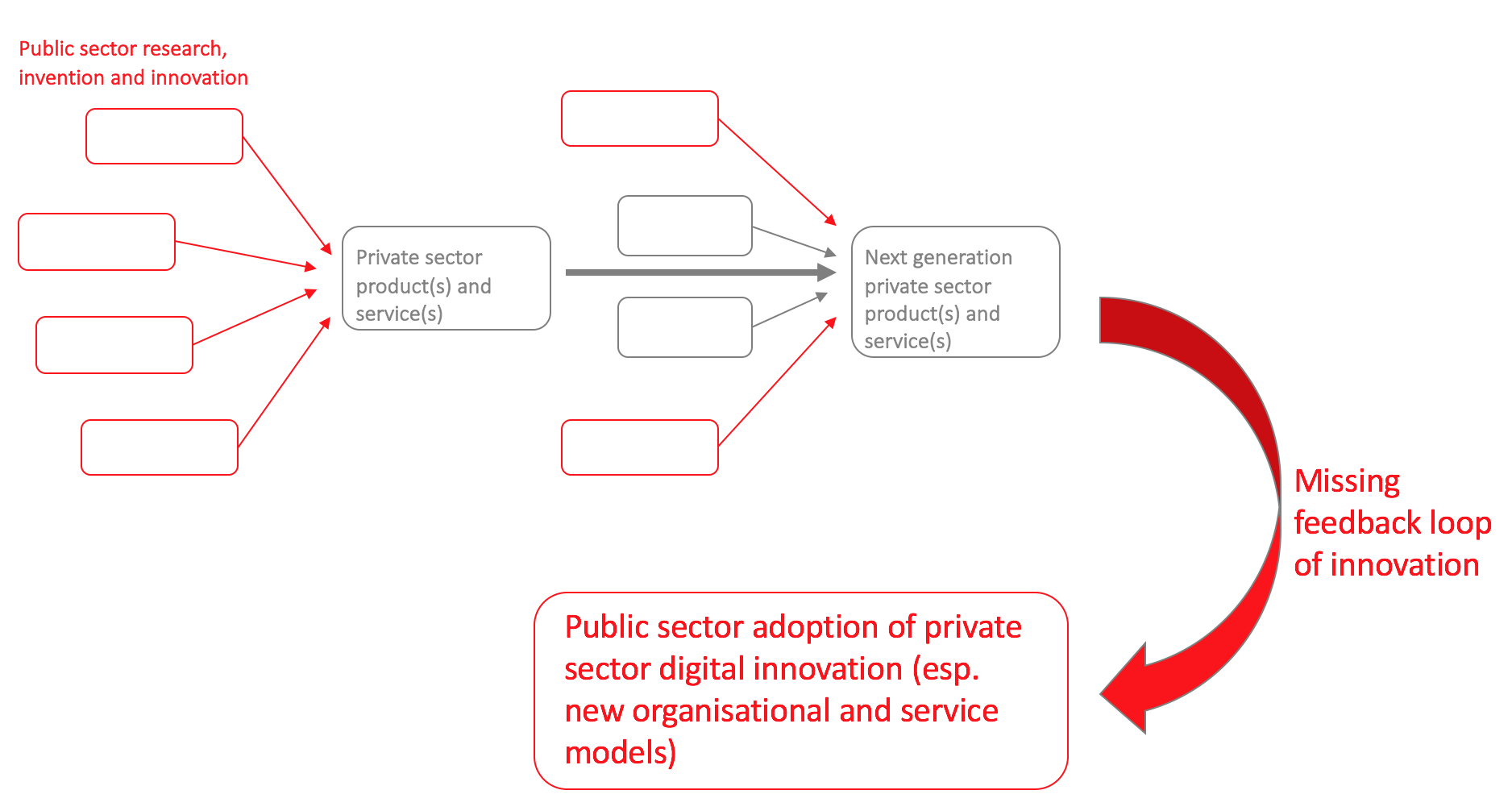

In her 2013 book “The Entrepreneurial State”, Mariana Mazzucato describes how it is the state that has often acted as the seed-corn innovator and investor of research and development – a role that has in turn enabled private sector companies to reap significant benefits in their own innovation and growth. Yet so far this flow of invention and innovation seems to have been largely one-sided, from state to private sector: the public sector is taking little benefit from the significant changes technology has brought to business models and the way organisations are now able to operate (much of it in turn enabled by better use of data). The public sector is still overly focused on that “Technology” ring in the first diagram above, and neglecting to work across all the other areas – as truly digital organisations do.

By ignoring these more important levers of reform, the result has been repeated attempts to build common technical infrastructure and shared technical structures at the centre of government with the assumption that somehow widespread improvements across our public sector will follow. There has been little focus on how to drive the wider, required changes indicated in that 1999 model above.

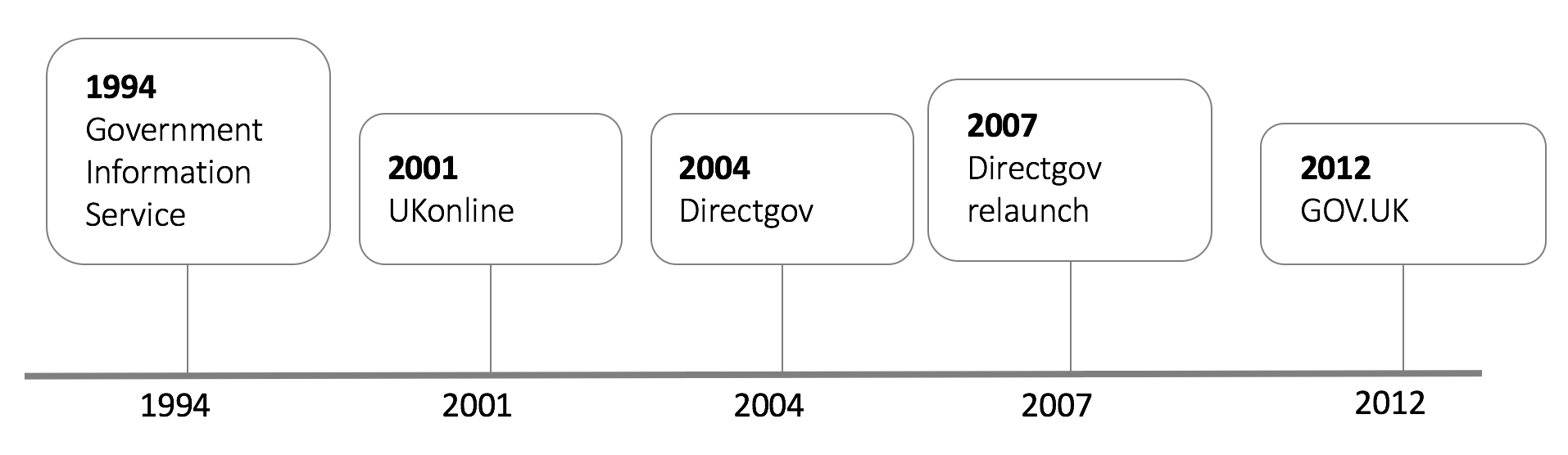

The wholesale opening up of government, promoted by both of the influential reports that lay behind recent reform efforts – “Better for Less” and “Revolution not Evolution” – has not happened. Outside of some of the main recommendations and influences that flowed from “Better for Less” – spend controls, open standards, disaggregation of monolithic contracts, adoption of public cloud, open markets and the encouragement of SMEs, etc. – the focus instead degraded to another generation of bespoke central infrastructure and in particular another repolished website. The opening up, through open APIs, was forgotten, as the recent National Audit report observed, yet arguably this would have been a far more effective way of genuinely beginning to help re-engineer our public services and organisations.

Far too often there has been a lazy and self-serving retreat into revamping and re-launching the central government website. This may make for comforting headlines, media visibility and good international PR, but does little to fundamentally improve the operations and services of the public sector.

The focus on so-called “service design” is often constrained, able to focus only on a subset of the design that’s necessary, and all too often dominated by a website-centric mindset. The result is endless existing forms and processes being placed online over the past 20 or so years, with the keyboard and screen simply a replacement for pen and paper and the central components designed to reinforce the current ways of working.

The result is an over-promised, over-hyped and often purely self-promotional myth of government “digital transformation“. It is a weak and unconvincing shadow of the digital services and organisational models elsewhere. Our public sector deserves far better than this endless cycle.

The focus needs to move well beyond the “Technology” layer (and its current superficial rebrand as “Digital”). It’s time the public sector ingested and adopted in-house many of the significant private sector innovations in terms of new organisational models and services that have grown from those seeds of investment and innovation originally planted by the public sector.

If we want technology-enabled reform and redesign of our public services and organisations to succeed, we need to stop chasing around in circles. We need an approach that spans at least the scope of the diagram at the start of this blog. Until that happens, technology in our public sector will continue to be a side-player tinkering on the margins, and propagating broken services, organisations and processes – when it should instead be guiding and leading it to fundamentally better ways of working.